Inbox Zero for Error Tracking

You might have heard of Inbox Zero: the idea that your email inbox shouldn’t be a dumping ground, but a place where every message is either handled, filed, or deleted. The goal is zero messages – not because you never receive any, but because you make clear decisions with regularity. You process. You don’t hoard.

Zero Errors

Like with email, applying this mindset to error tracking can change how you work. You can treat your error tracker like an inbox. Every new issue: fix it, investigate it, or mute it if it’s irrelevant. The goal is zero unresolved errors – not because your code is flawless, but because nothing lingers without a decision.

It’s not about urgency. You don’t have to check constantly. Once a day, once a week: what matters is returning to zero with some rhythm.

Keeping up reduces mental clutter. You’re no longer carrying around “I should really look at those.” You’re not wondering if you missed something important. You’re not letting issues pile up until they become overwhelming.

You’re not buried in leftovers from last week. You check in, see what’s new, and get to work. That clarity helps you focus on what matters right now.

The best dashboard is no dashboard

Inbox Zero means you don’t need dashboards, graphs, or metrics before you can act. If you treat every incoming error as worth reviewing, you don’t have to count occurrences or debate priorities. You just look at the error, decide if it’s relevant, and act.

That’s not to say frequency never matters. But one error that fires once – silently dropping a customer’s payment – is

worse than a TimeoutError that happens hundreds of times while polling a flaky third-party service. Severity isn’t the

same as volume.

If you’ve reviewed an error and muted it, great. The point is: you looked. You didn’t ignore it just because it didn’t show up in a chart.

Early is better

Bugs tend to snowball:

- A failing background job might quietly leave user records half-finished, causing subtle breakage elsewhere.

- An exception in a database migration leaves a column in an unexpected state, breaking unrelated features days later.

Catching errors early means you don’t build more features on top of something that’s already broken. Even if you don’t fix it right away, you avoid making the situation worse by ignoring it.

Compare this with how you handle problems in your CI pipeline. You wouldn’t ignore failing tests: they stop the build, create urgency, and demand attention. That mindset works for production errors too. Because they’re both early signals that something no longer behaves the way you expect.

Ready to act

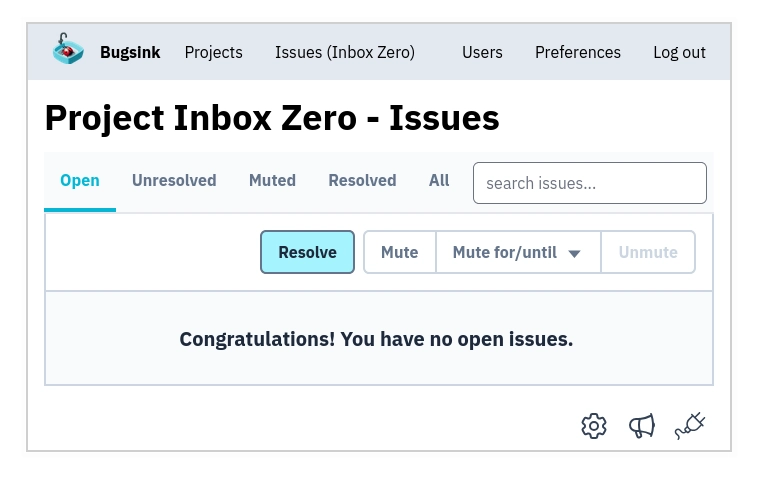

When you open your error tracker, you only see items that need attention – without first sifting through a pile of unresolved issues. You’re not looking at a sea of red and wondering where to start. There’s no need to scroll past weeks of noise or guess which errors are still relevant.

Sometimes that means reacting fast: a real error just landed, users are affected, and someone needs to dig in. You don’t want to spend that moment filtering duplicates or guessing what’s already been handled. The list is short, current, and actionable.

Other times, it’s part of the routine of checking in once a day or once a week. You skim the list, fix what needs fixing, mute what doesn’t matter, and move on.

Focus and flow

But beyond practical benefits, there’s something more personal: the way it feels to work like this. A cluttered error tracker, like a cluttered inbox, wears you down. Each unresolved item is a small, lingering decision. It nags. It makes you second-guess whether you’re still on top of things.

Clearing them resets the mental state. You’re no longer wondering what you’ve missed. You’re not reacting, you’re choosing. It’s the difference between firefighting and building with intent.

And that moment when you do reach zero? It’s rewarding. You see it clearly: no loose ends, no unknowns. You’re not behind. You’re ahead.

When not to do this

There are situations where Inbox Zero for error tracking simply doesn’t make sense – and trying to force it will waste your time.

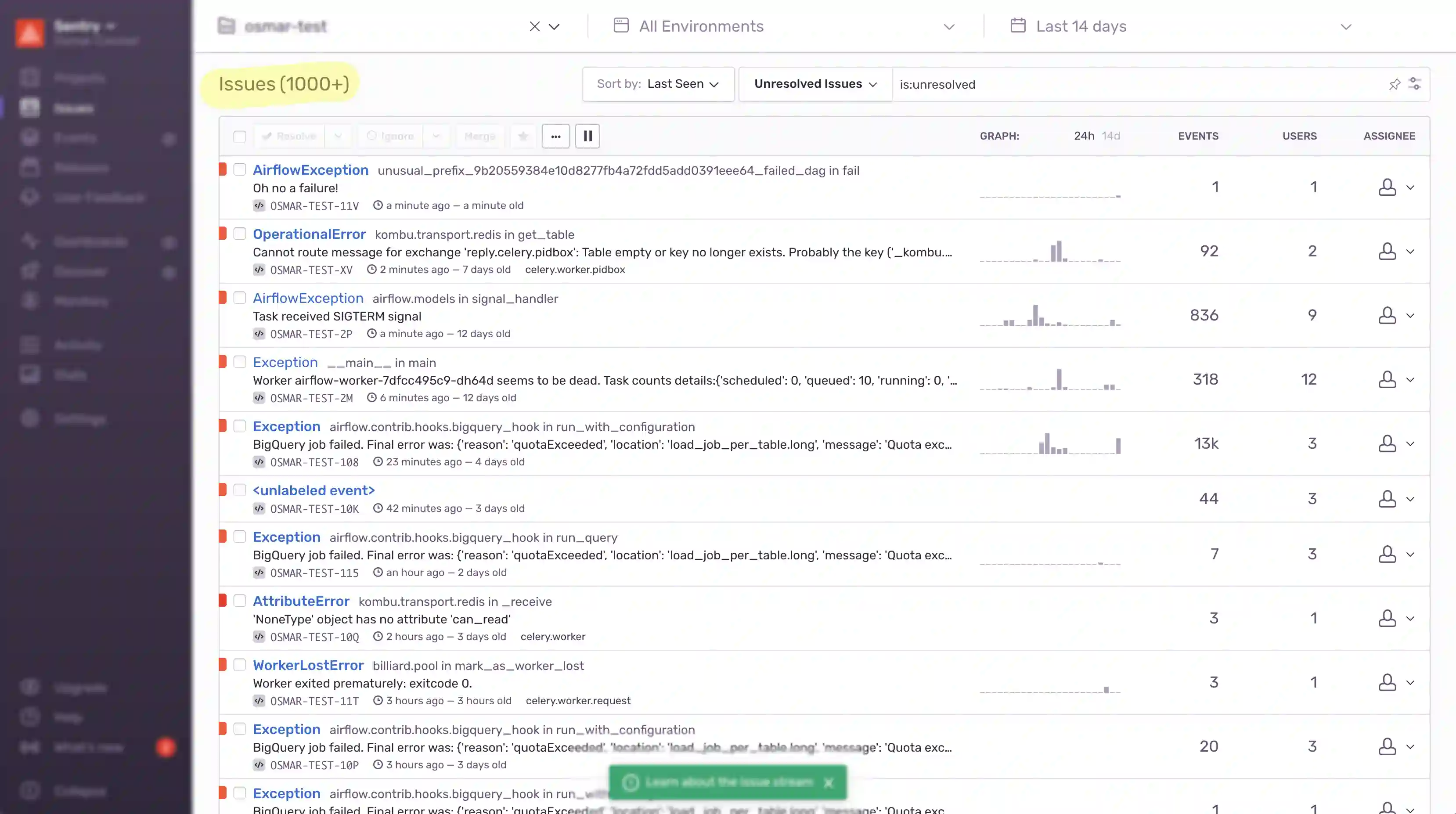

Some environments are just too noisy. In frontend-heavy apps, you’ll see exceptions from browser extensions, corrupted localStorage, weird Android builds – errors you didn’t cause and can’t fix. They flood your inbox with junk. Trying to handle each one isn’t discipline. It’s busywork.

Other times, the errors don’t matter enough – not because they’re harmless, but because the entire app isn’t critical. Maybe it’s an internal tool used once a quarter. Maybe it’s a system nobody relies on. A report fails, a settings page crashes, and nothing breaks that people actually care about. Treating these like frontline systems just burns time. Inbox Zero here looks tidy, but doesn’t help the business.

And sometimes, the broken part isn’t even yours. A third-party service flakes out. You didn’t build it, and you can’t fix it. Still, you might own the way you use it. If the failure shows up in your app, make sure your side handles it cleanly. Notify them if needed. Then move on. Tracking every outage like it’s your responsibility just adds noise.

In all of these cases, Inbox Zero doesn’t apply. Trying to force it won’t help. It just makes you look organised while nothing changes.

What I do

Everyone ends up with their own rhythm. Here’s what that looks like for me:

For errors in Bugsink itself, whether I’m dogfooding or looking at hosted installs, I care about every single one. These affect real users, including me, so I want a clean slate. Inbox Zero makes sure nothing slips through.

In local development, I take a different approach. Errors pile up, and that’s fine: they’re transient, and I know to look at the top. The rest just drifts down and eventually disappears.

By the way, this mindset didn’t start with Bugsink. At previous jobs –big orgs with lots of moving parts – I’d often get asked to take a quick look when something wasn’t working. More often than not, the answer was sitting in the error tracker: an API call that failed, a background task that quietly stopped running. Nobody had looked. The signal was there, but nothing had been done with it.

Tools for Inbox Zero

Not every project needs Inbox Zero, but your tools should support it when you do.

A clean UI, clear resolution options, and support for muting known cases – these sound basic, but they’re not universal. Some trackers treat a short list like a failure mode. You get empty graphs, filters, and triage widgets meant for high-volume noise. Even with just one or two issues, the interface feels cluttered.

Worse, some tools automatically assign priorities and then apply filters based on those priorities. You might be missing real issues, not because you resolved them, but because the UI quietly hid them. It’s hard to tell whether you’ve actually reached zero, or just filtered your way into thinking you have.

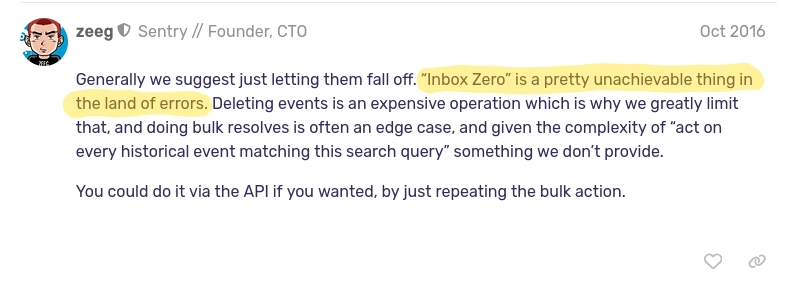

This isn’t a mistake — it’s by design. The founder/CTO of the biggest player in the market has said Inbox Zero isn’t a real use-case and it shows.

Conclusion

Inbox Zero for error tracking means no backlog, no guessing what still matters, and no time wasted scanning noise. You know what’s broken, handled, and what you’ve chosen to ignore.

That kind of clarity speeds you up. You’re not sorting through clutter or working around your tools – you’re fixing things. It also feels better. You’re not behind. You’re not wondering what you’ve missed. You’re done.

Not every app needs this, but when it fits, it makes both the work and the workflow lighter. And your tools should support that, not fight it.